Business Blunders Hall of Shame

From magnate to inmate: These are the nation's most notable white-collar convicts

A lot of kids learn their first business lessons playing Monopoly.

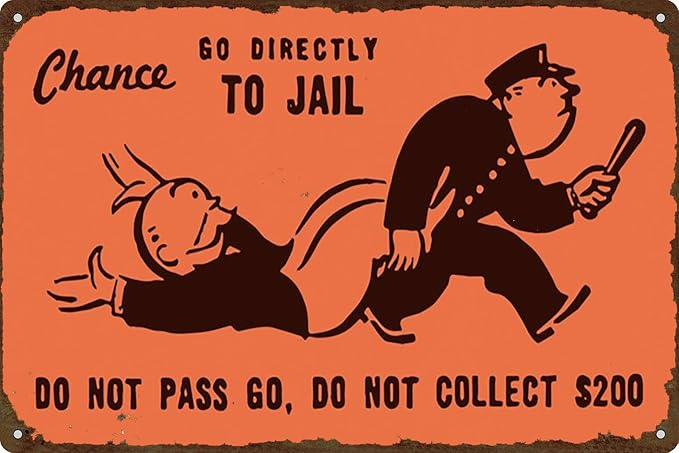

They throw dice, slide game pieces and buy properties. They pay rent, fees, fines and taxes as they go. Inevitably, they draw a bad card:

This may not seem right to a child. They may know business people from their schools, neighborhoods and places of worship. They may know that business people create jobs, fund charities and support communities. Who would put them in jail?

But the Monopoly game, which dates back to 1902, isn’t cynical. Every business is a potential honeypot for criminals. And business leaders who may once have been respected as pillars of their communities can indeed end up in handcuffs and orange jumpsuits.

Welcome to the Business Blunders Hall of Shame

White-collar felons offer cautionary tales for investors, lenders, customers, employees and other stake holders. They provide object lessons for anyone tempted to cut corners too sharply. And they stand as nauseating examples of just how crooked our economic system can be without adequate controls.

Some of these names you’ll remember, some you may have long forgotten, some you may have never heard about. Have a laugh or a cringe at the follies.

For these folks, there was never any “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

Accepting nominations

The Business Blunders Hall of Shame considers white-collar offenders large and small, famous and obscure, past and present. It is an ongoing effort with new inductees added sporadically, so check back for updates.

Paid subscribers can leave nominations in the comments section:

To qualify, past and present inductees must have:

Been convicted of a felony.

Displayed astonishing greed, stupidity, recklessness, hypocrisy or abhorrent behavior.

Left a trail of tears.

Inductees

Welcome to the Business Blunders Hall of Shame. Here’s a list of who has been included so far. Paid subscribers can skip to an inductee by name using these links below, or keep scrolling to tour the entire ignominious assembly.Antar, Eddie - Crazy Eddie

Business Blunders maintains awareness of the follies that plague America’s financial system. Please help make the business world a more honest, less reckless, less authoritarian place by:

Liking and commenting on posts, which boosts the Substack algorithm.

Sharing this newsletter with friends and associates.

Subscribing. Free or paid, I’m so glad you’re here.

--Robert Brennan, First Jersey Securities. Fraudster.

--Joseph Jett, Kidder Peabody derivatives trader; cost the firm millions and it had to be sold

--Nick Leeson, Barings derivatives trader who brought down the bank

--Angelo Mozilo; non-doc subprime mortgages played huge role in the financial crisis

Gee, what's the name of that guy with orange hair that will once again pretend that he plays a president on TV??!! Ya, that guy hits all the marks!