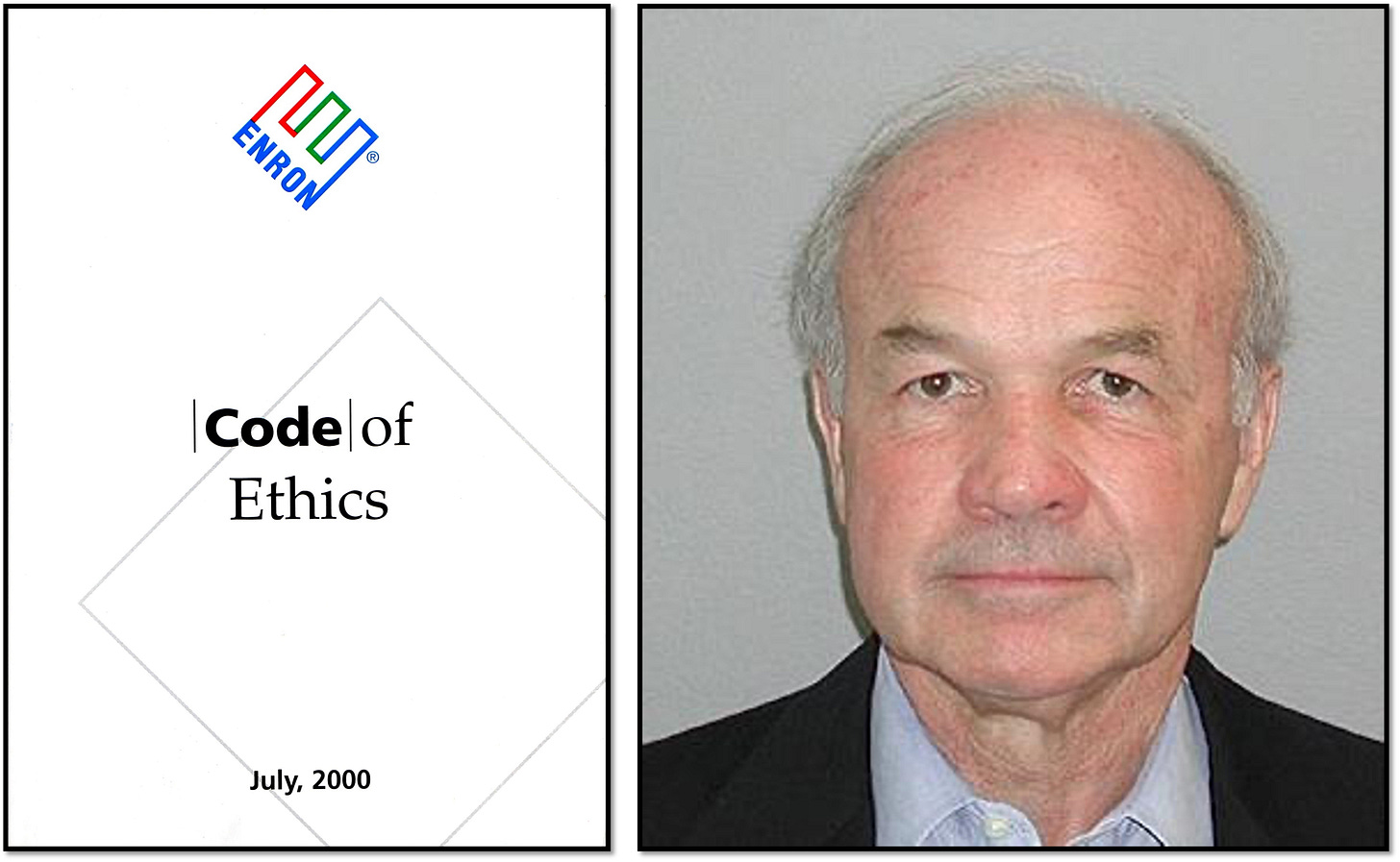

Enron founder and chairman Ken Lay had to take the helm when CEO Jeffrey Skilling abruptly jumped ship on Aug. 14, 2001.

“We regret Jeff’s decision to resign, as he has been a big part of our success for over eleven years,” Lay told investors at the time. “But, we have the strongest and deepest talent we have ever had in the organization, our business is extremely strong, and our growth prospects have never been better.”

It was a big lie, especially for the son of a Baptist preacher, and Lay had only a snowball’s chance in hell of getting out of it.

Read More: Enron Was A Parody Of Itself (Business Blunders)

On Dec. 2 of that year, the company filed bankruptcy and was soon exposed as one of the most massive accounting frauds of all time.

More than 20,000 employees lost their jobs, and in many cases their life savings since their retirement accounts were loaded with Enron stock. Investors all around the world lost billions.

At trial, Lay’s defense attorney Michael Ramsey played the Christian card.

“He is probably the biggest pillar that the … First Methodist Church has here in Houston. And Ken Lay, believe me, is not a courthouse Christian. There are so many people who get religion when they come to court – they haven’t had it all their lives – that I am proud to represent somebody that has been bone-solid church-bound all his life.”

Bankruptcy wasn’t a crime, Ramsey argued. This was all just an economic accident. A panic.

“I firmly believe I am innocent of the charges against me as I’ve said from Day One,” Lay said, walking out of a Houston courthouse during his trial.

Lay was convicted on numerous felony charges. Still, he maintained his innocence and ultimately scored a dismissal, but in a rather unfortunate way.

Shortly after his conviction, Lay flew to Aspen, Colo., for a summer vacation before his sentencing. Then he died of a heart attack. His conviction was thrown out on the technicality that dead men can’t appeal.

Which goes to show that a snowball’s chance in hell is still a chance.