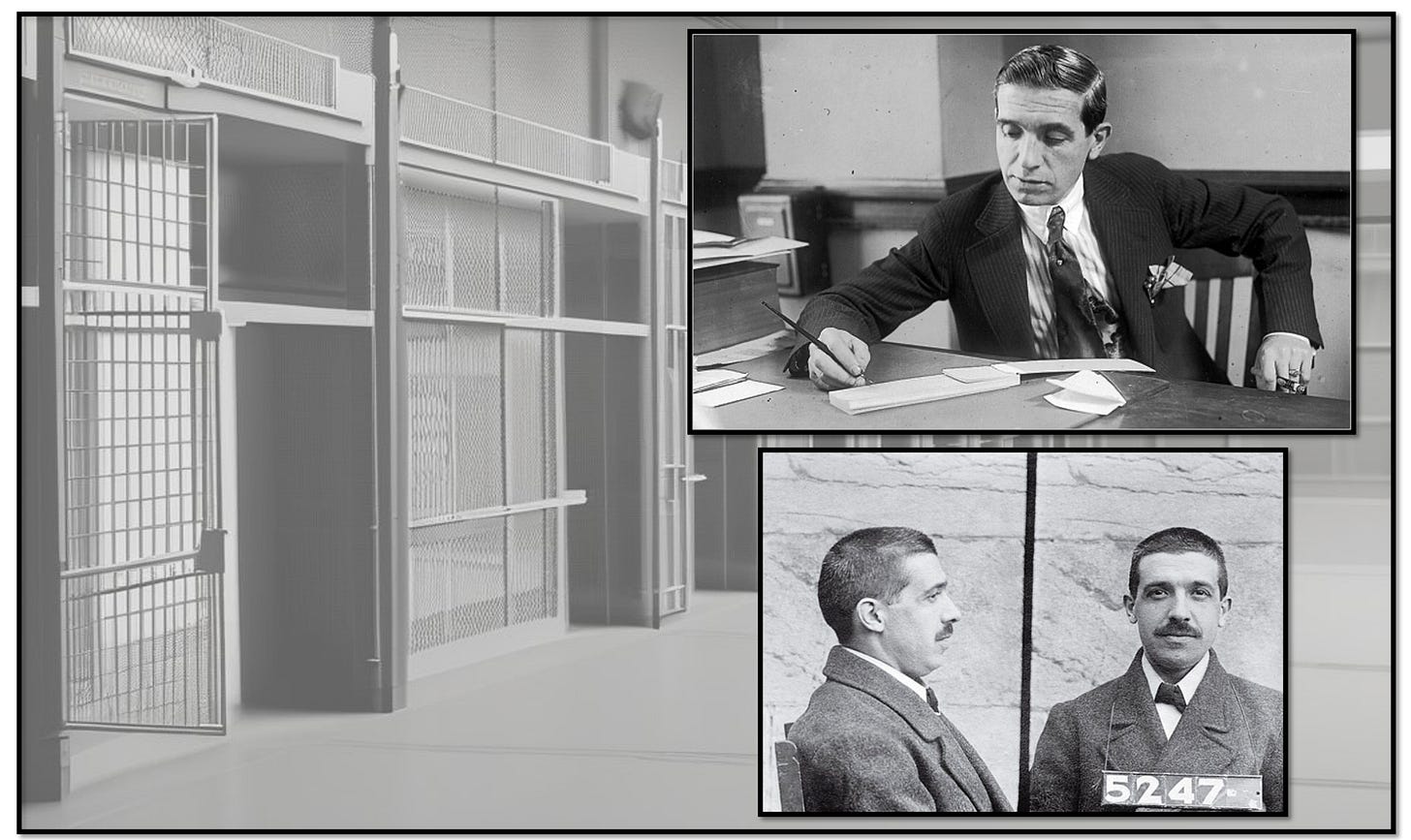

Charles Ponzi – Boston Swindler

When police investigated, they decided to invest. Benito Mussolini gave him a treasury job. People can't stop falling for his signature fraud.

Hardly a week goes by before prosecutors or regulators expose a new a Ponzi scheme. Italian immigrant Charles Ponzi didn’t invent this classic grift, but in the 1920s he ran it so well that he branded it for perpetuity.

Read More: 15 Tales Of Lost Ponzi Riches (Business Blunders)

Countless scams later, you never hear anyone say they got taken in a Madoff scheme. Even after Bernie Madoff took investors for so much more, they still call it a Ponzi scheme.

Ponzi promised clients a 50% profit within 45 days or 100% profit within 90 days.

He made the ridiculous claim that he could buy postage coupons in other countries and cash them out in the U.S. for more – but he did none of this. His scam ran for more than a year before it collapsed, costing his victims $20 million.

Ponzi’s scheme and all that followed are so childishly simple that it’s a testament to human stupidity and greed that anyone still falls for them.

Perpetrators typically promise investors outsized returns. They may then make good on these promises to early investors, who are then easily conned into reinvesting and telling their friends to invest as well. New money goes to pay off old investors as the scammers skim the pot until the inevitable collapse.

Typically, these frauds require a charmer with remarkable sales skills. Someone who smiles at adversity and oozes delusional confidence. Someone like a CEO. Someone like Charlie Ponzi.

Ponzi’s father was an Italian army general who sent him to a French boarding school. There, he cultivated aristocratic airs. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1903.

“I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes, and those hopes never left me,” he once told The New York Times.

He stood only 5-feet-2 but maintained a grand presence. He wore expensive suits and swung a gold-headed cane as he strode the streets of Boston.

Money poured in so fast, Ponzi’s employees collected it in wastepaper baskets.

Ponzi became a celebrated business genius. He bought a mansion, jewels for his wife, and a limousine. He got fat lines of credit from banks. He even acquired a controlling interest in the Hanover Trust Co. with $3 million in a suitcase.

He was so convincing that even police who examined his company decided to invest.

A Boston newspaper pointed out that Ponzi’s claims didn’t add up – you can’t make millions of dollars trading stamps for pennies. But for a time, Ponzi always paid. So Bostonians cheered him and booed the newspaper. (You can still hear it from suckers today: Fake news! Fake news!)

Later, Boston newspapers reported that Ponzi had run a similar scam in Montreal and had been sentenced to 20 months in prison for forgery. Ponzi insisted the story was false. But by then his scheme was unraveling.

Ponzi went to prison again for what became his signature fraud. Upon release, he ran a swampland scam in Florida.

“I went looking for trouble, and I found it,” he once said.

Eventually, Ponzi was deported to Italy. Then Benito Mussolini gave him a treasury job, believing him to be an international banker.

Later, Ponzi worked for an Italian airline that flew to Brazil. There, he demanded bribes from people smuggling money.

Ponzi spent his last months as a charity patient in a Rio de Janeiro hospital. He died in 1949 at the age of 66. But he must have known he’d earned his place in history. In one of the last photos taken of Ponzi, he is propped up in his hospital bed, and he is smiling.